genre transcendence

on defying classification with Patti Smith

There's a certain anxiety that arises when someone asks, "What do you do?"

The question hangs in the air, demanding categorization - strategist, writer, athlete, academic, artist - as if human experience could be neatly filed away in manila folders. I've been thinking about this lately, particularly during these January days when everyone seems obsessed with defining their purpose, plotting their paths, fitting themselves into pre-existing boxes.

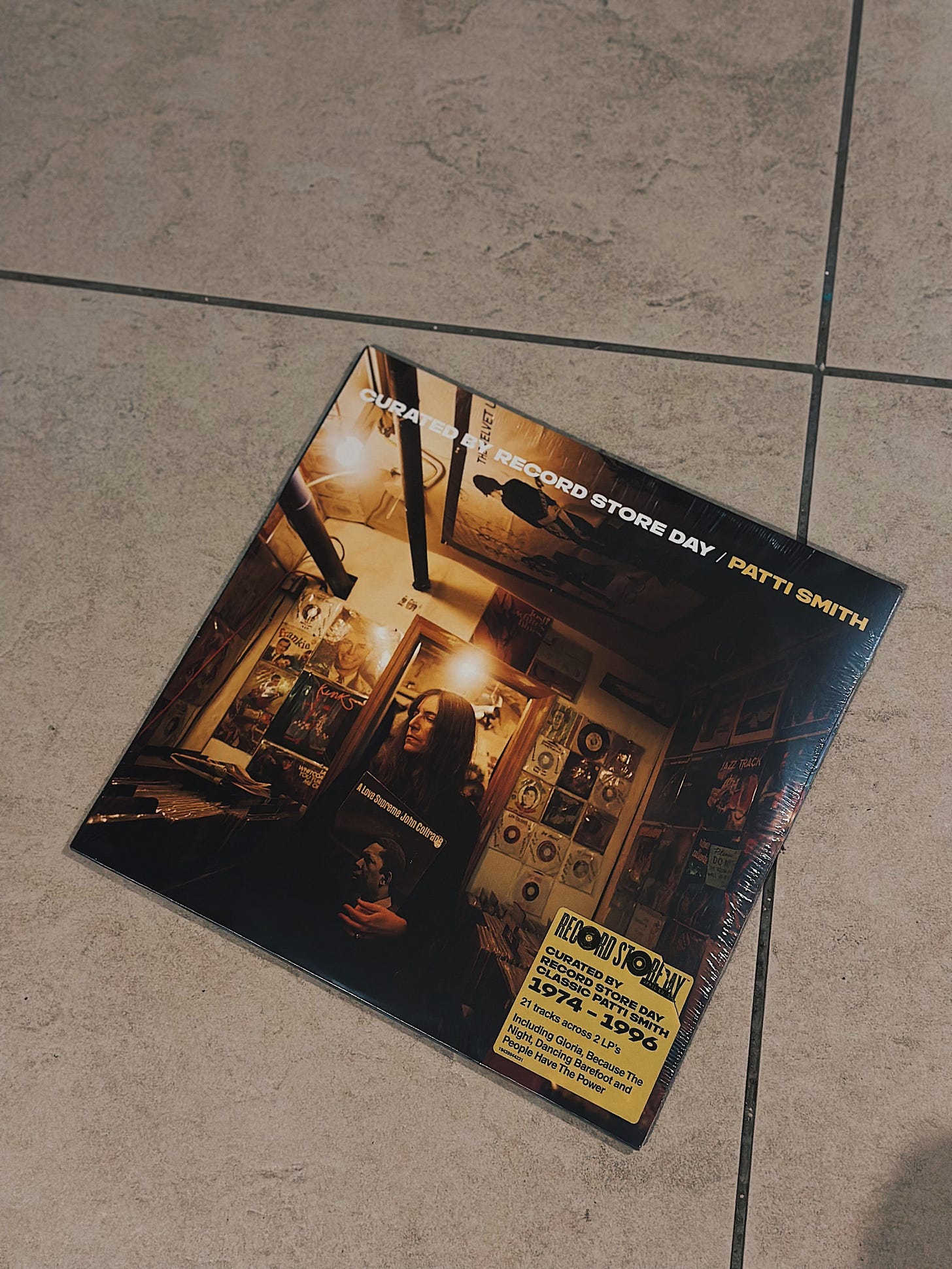

Last night, sitting cross-legged on my floor with Horses playing for perhaps the thousandth time, I found myself wondering when exactly we became so obsessed with categorization, with the need to label and separate and contain. The question emerged from a year of watching my own life resist neat definitions - shifting between roles and identities - and finding solace in artists who taught me how to exist in these in-between spaces.

Because there are artists who change how we think, and then there are artists who change how we breathe. Patti Smith belongs to the latter category. I've spent months trying to write about what she means - not just to art or music or literature, but to the very act of existing authentically in the world. Every attempt feels inadequate, like trying to capture twilight in a mason jar. Yet perhaps this very inadequacy is the lesson - that some things, some people, some ways of being, demand we learn to live without the comfort of clear categorization.

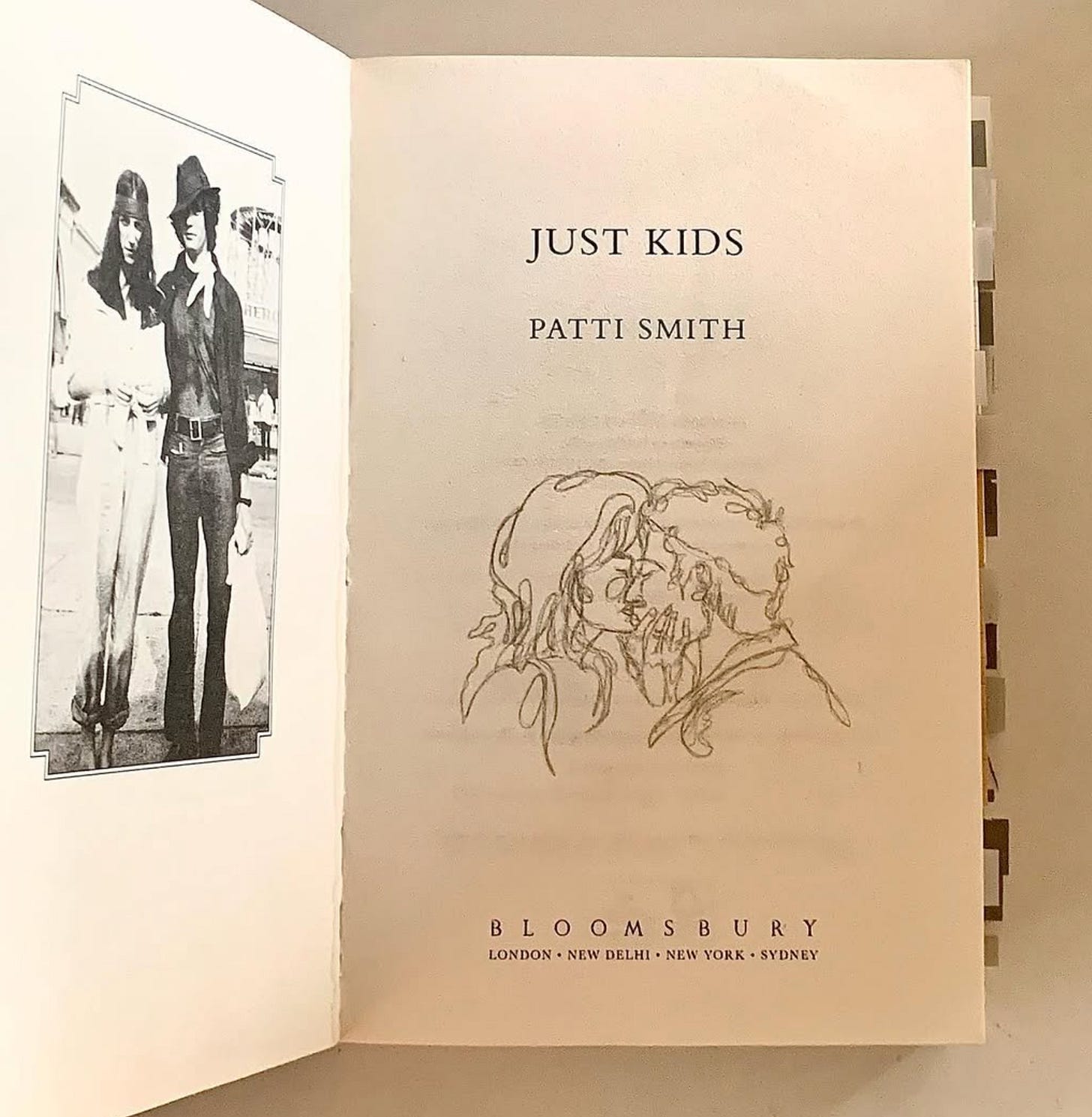

You see, Patti has always existed beyond these boxes, moving through the world with a freedom that feels almost mythological in its rarity. The first time I encountered her work was through her book, Just Kids. It was propped up on a shelf at Blossom Book House in Bangalore, and something about her face on the cover - those dark eyes that seemed to look through you rather than at you - made me pause. I didn't know then that picking up that book would be one of those moments that divides your life into before and after.

What struck me wasn't just the writing, though God, the writing. It was the way she moved through the world - this strange and beautiful creature who seemed to exist in a space between spaces. Here was someone who understood that art isn't about fitting into pre-existing categories but about creating new ones, about making space for the ineffable.

Last week, sitting in a theatre in my city, I watched a classical violinist perform a piece that wove together Carnatic ragas with jazz improvisation. The audience seemed initially unsettled - was this classical music? Was it jazz? Their discomfort was palpable until the moment they stopped trying to categorize what they were hearing and simply let themselves experience it. Something shifted then - in the music, in the room, in our collective understanding of what was possible.

We talk about transcending categories like it's a kind of escape, using the language of breaking free: shattering boundaries, breaking molds, thinking outside boxes. But I'm beginning to wonder if true transcendence isn't about escape at all - it's about presence. About inhabiting the spaces between with such fullness that they become spaces in their own right.

This hit home recently when I found myself explaining my work to my cousin. Children, I've noticed, have no trouble understanding transcendence. They don't see why someone can't be a doctor and a dancer, a teacher and a trapeze artist. It's only as we grow older that we learn to limit ourselves, to choose one path at the expense of others. We're taught that specialization equals success, that clarity comes from narrowing rather than expanding.

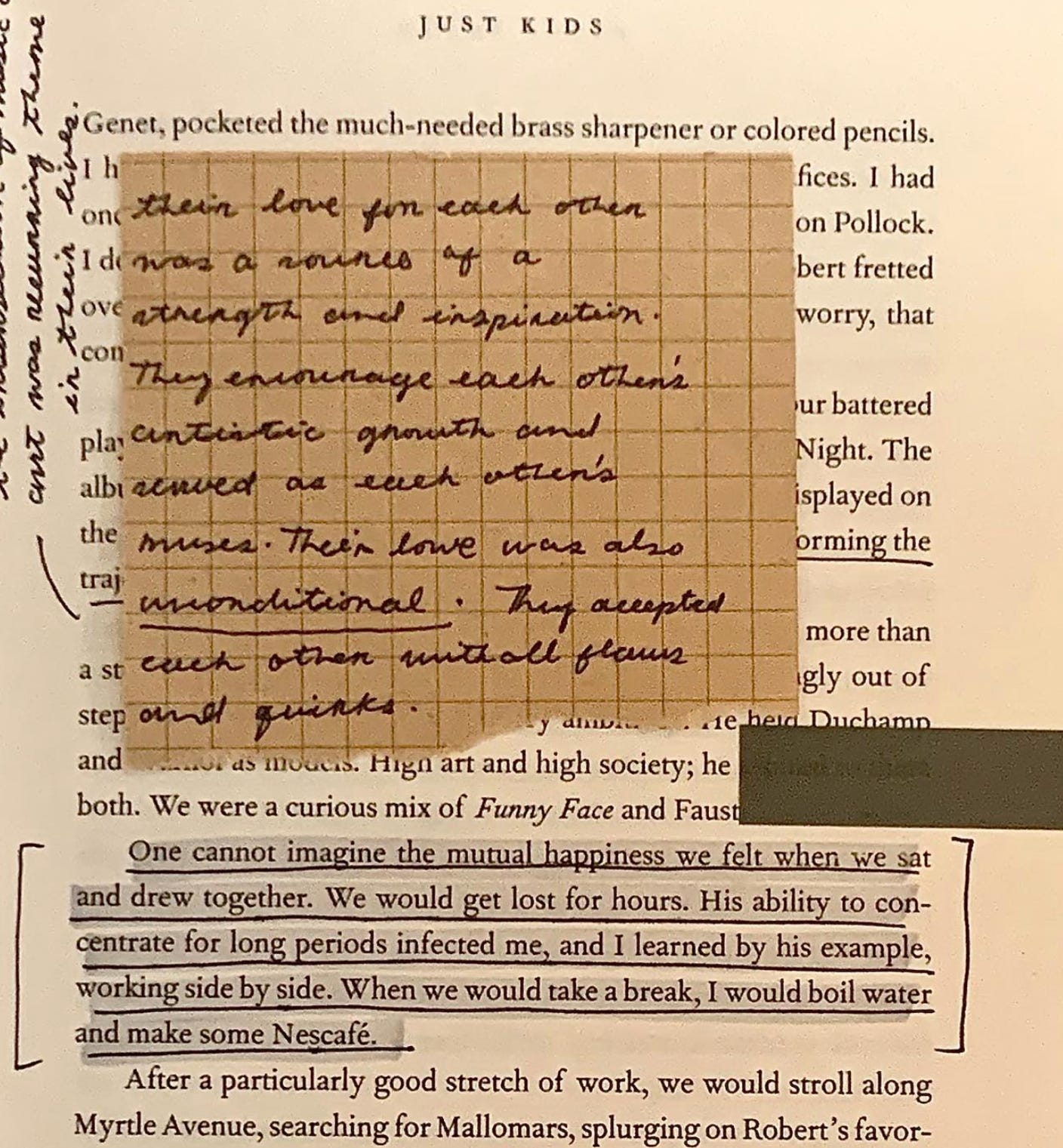

In those early days at the Chelsea Hotel, Patti would write poetry in the morning, make drawings in the afternoon, and perform at night. There was no separation between these acts of creation - they all flowed from the same source, like different tributaries of the same river. She didn't care about being called a poet or a musician or an artist. She just wanted to make things that hadn't existed before.

The Japanese have a concept called "ma" - the meaningful space between things. It's present in their architecture, their music, their art. It's the pause between notes that gives music its rhythm, the empty space in a room that makes it inhabitable. Perhaps transcendence lives in these spaces - not in the categories themselves, but in the fertile ground between them.

I see this in the most vibrant minds I know. They are businesspeople who write poetry, scientists who paint, teachers who never stop being students. They move through the world not like specialists but like renaissance souls, drawing connections between seemingly disparate fields, finding patterns in the chaos. Their power doesn't come from mastering a single category but from their ability to exist meaningfully in the spaces between.

What's fascinating is how this relates to agency and purpose. We often think of transcendence as a kind of freedom from definition, but paradoxically, it requires tremendous intention. To exist between categories means actively choosing to resist the comfort of clear labels. It means being willing to live with ambiguity, to embrace the discomfort of being hard to define.

The digital age both helps and hinders this understanding. On one hand, it allows for unprecedented crossing of boundaries - we can be global citizens, digital nomads, remote workers. On the other hand, its algorithms constantly try to sort us, to predict us based on past behavior, to put us in ever more specific boxes. Each click, each like, each purchase becomes another data point attempting to define us.

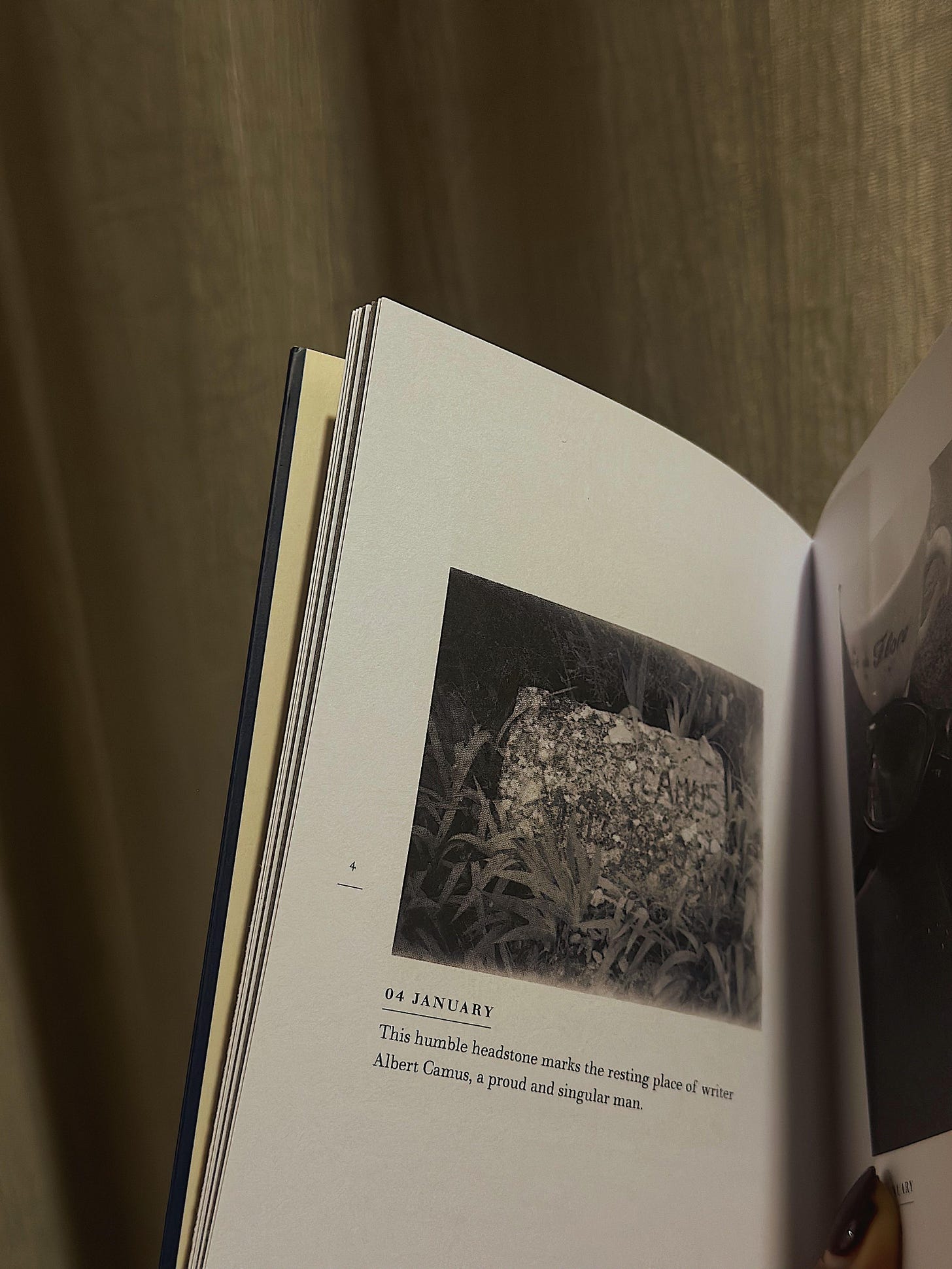

I think about how Patti moved between mediums with such grace - poetry becoming song becoming visual art becoming prose. There's something almost alchemical about this ability to transmute one form of expression into another. This morning, studying her photographs - those black and white images that feel like visual poems - I'm struck by how the same hand that wrote Because the Night also captured Virginia Woolf's cane, Arthur Rimbaud's fork, Roberto Bolaño's chair. These aren't just photographs - they're meditations, prayers, songs without music.

But here's what I'm learning: transcendence isn't about rejecting categories entirely. It's about understanding them as tools rather than truths. They are useful for organization but should never become prisons. The most interesting work happens when we use categories as launching pads rather than boundaries - when we understand them well enough to move beyond them.

This relates deeply to how we think about purpose. We're often told to find our "one true calling," as if purpose were a single fixed point rather than a constellation of meaningful engagements. But what if purpose isn't about narrowing down but about opening up? What if it's not about finding your category but about creating your own space between existing ones?

I see this in my own work, in the way writing feeds into photography feeds into teaching feeds back into writing. These aren't separate pursuits but different manifestations of the same underlying impulse - to understand, to connect, to create meaning. When I write, I'm also painting with words. When I photograph, I'm writing with light. When I teach, I'm learning. The boundaries between these activities begin to blur, revealing themselves as artificial constructs rather than natural laws.

Last month, going through old journals, I found a note I'd written to myself years ago: "Your inability to fit neatly into categories and stereotypes isn't a flaw." At the time, I think I was trying to comfort myself. Now I see it as a kind of manifesto. Because existing between categories isn't just about personal freedom - it's about creating new possibilities for everyone. Each act of transcendence creates space for more transcendence, widening the field of what's possible.

What strikes me most about Smith's work is its profound democracy of reverence. She approaches Herman Melville's grave with the same devotion she brings to her morning coffee ritual. This isn't just artistic versatility; it's a radical philosophy of attention. In Devotion, she writes about her creative process with such transparency that the line between making art and being alive completely dissolves.

This kind of attention - this ability to see the sacred in the everyday, to find connections between seemingly disparate things - is perhaps what we're really talking about when we talk about purpose. It's not about fitting into a predefined role but about bringing your particular way of seeing to everything you do.

I think about the times I've felt most alive, most purposeful. It's never been when I was successfully fitting into a category, but rather when I was creating something new in the spaces between. Like last week, when I combined my love of photography with my practice of teaching, creating a visual literacy workshop for high school students.

The cost of transcendence is certainty. When we step beyond established categories, we lose the comfort of clear definitions, of knowing exactly who we are and what we do. But what we gain is the freedom to explore, to evolve, to surprise ourselves. There's a liberation in realizing that we don't have to choose between being a writer or a photographer, an academic or an artist, practical or creative. We can be all of these things, and in the spaces between them, we might find something entirely new.

In Buddhism, there's a concept called "beginner's mind" - the ability to approach each moment fresh, without preconceptions. This might be the key to both transcendence and purpose: maintaining the ability to see things anew, to question our categories, to remain open to possibility.

The sun is setting now, casting long shadows across my desk where Just Kids lies open next to my notebook. Patti Smith's voice drifts from my speakers, reminding me that some of the most profound truths exist in the spaces between categories, between notes, between words.

Perhaps that's the ultimate lesson about purpose and transcendence - that they're not about rising above or moving beyond, but about moving through, about being fully present in all the spaces we inhabit, even (especially) the ones that don't have names yet. It's about understanding that our lives, like all great art, resist easy classification.

So maybe the next time someone asks "What do you do?" the anxiety doesn't have to come. Maybe instead there can be a kind of joy in the inadequacy of any simple answer. Because the truth is, we do many things. We are many things. And it's in this multiplicity - this refusal to be easily categorized, even by our profession - that we find our most authentic expression, our truest purpose.

The challenge, then, isn't to find our box but to live meaningfully in the spaces between boxes. To create new spaces. To make peace with ambiguity. To understand that purpose isn't a destination but a way of moving through the world - with attention, with reverence, with the courage to resist easy categorization.

As night falls and the city lights begin to twinkle, I think about all the categories I've tried to fit into, all the boxes I've tried to check. And I think about how liberation came not from finding the right box but from giving myself permission to exist in the spaces between. Like Patti Smith writing poems in the morning and singing rock and roll at night, like the violinist weaving together classical and jazz, like all the beautiful misfits who've shown us that the most interesting things happen when we stop trying to fit in and start creating our own spaces to exist in.

Perhaps this is what purpose really means - not finding your place within existing categories, but having the courage to create new ones. To live in the questions rather than the answers. To make your home in the spaces between.

Hi friends, writing this piece has opened up so many questions about how we define ourselves and our purpose. I keep thinking about the spaces between - how they terrify and liberate us in equal measure. There's more to explore here, particularly about how this resistance to categorization shapes our relationships and creative work. I'd love to hear from you: where in your life have you felt the tension between fitting in and transcending categories? When have you found freedom in the spaces between?

P.S. If you found meaning in these words, please consider sharing Mind Maps with others who might be wrestling with similar questions. This space thrives on curiosity and connection.

Your support through likes, shares, and subscriptions helps this little corner of the internet grow. Thank you for being part of this space!

Hi Ananya

Absolutely loved this. "Your inability to fit neatly into categories and stereotypes isn't a flaw" is a priceless advice. I have often felt uncomfortable while answering questions like what do you do, because there is no proper answer. There are so many things, and there are so many others I haven't done that would like to add to the answer.

Thank you for writing this. I am now more at peace being a Jack of many trades.